elsa o’brien lópez

When children are asked to learn a language in a very structured way from a very early age they’ll be asked to use skills they don’t possess yet and won’t be developing till later on in life.

For some time now, this has been a question asked and answered by many parents, teachers and experts, upon which they have often agreed to disagree. The most frequent answer is that the earlier a child starts to learn a second language, the higher the chances will be of them reaching native-like proficiency.

Contrary to popular belief, adults can actually learn a second language faster than children in certain settings. What research has shown is that this highly depends on the learning context.

Adults can learn a second language faster in a structured setting. This would be the classical classroom in which a language is presented step by step. The focus is generally on accuracy and in order to achieve this the learner will be frequently corrected. Learners will be presented with a narrower range of discourse types, probably only one native or proficient speaker and during a limited amount of time. The teacher will generally modify their input to make comprehension easier and will sometimes even use the learners mother tongue.

On the other hand, Carmen Muñoz, admits in her book Age and Rate of Foreign Language Learning (2006) that research carried out in contexts such as immigrants in natural settings and children in school immersion settings, seem to have proven that those who start to learn a second language at an early stage in life will often reach higher levels of proficiency in it than those who start later.

Why this difference in the rate of learning?

Krashen et al. (1979) made an essential distinction between ultimate attainment and rate. As it has been proven, older learners do have a higher learning rate in certain environments, whilst younger learners have shown to be slower at the beginning, but eventually show a greater level of ultimate attainment. This was considered evidence for the existence of a critical period. This period has been believed to be the limit beyond which learners of a second language cannot achieve native-like proficiency. Nowadays, due to a lack of consensus around the concept of a critical period and the ability of some learners to reach native-like proficiency at later stages in life, we speak of sensitive periods.

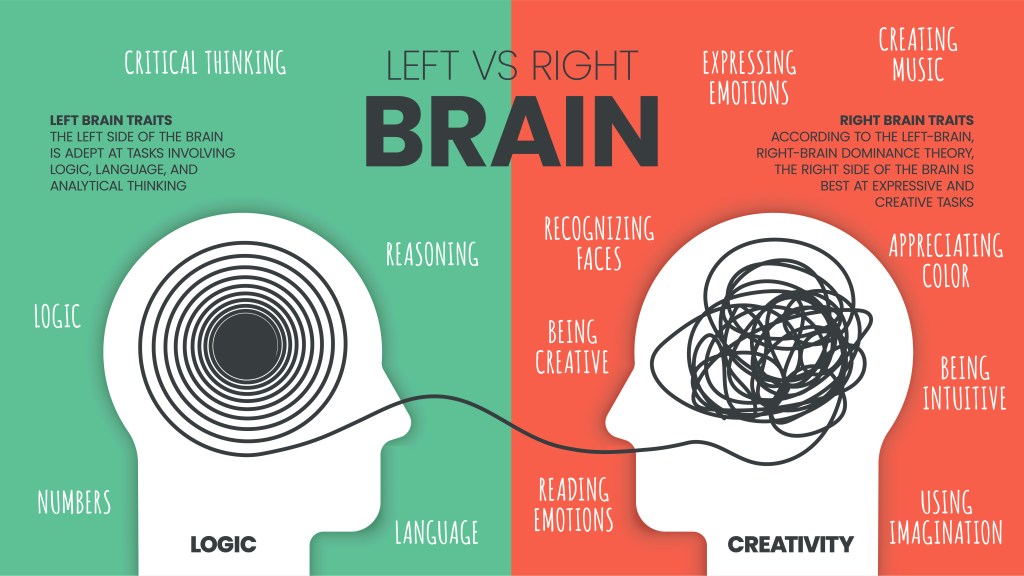

Although this might seem like contradictory evidence, what it points towards is different ways of learning. DeKeyser (2000) claimed that ‘somewhere between the ages of 6-7 and 16-17, everybody loses the mental equipment required for the implicit induction of the abstract patterns underlying a human language’ (200:518). The key message is that children’s superiority in learning languages is closely linked to the use of implicit mechanisms. It has even been pointed out that very young learners rely upon intuition, musicality and other skills controlled by our right brain hemisphere.

Adults, on the other hand, use analytic skills and logical thinking. Drawing on their cognitive maturity and existing language skills from their first language, adults can initially learn a second language at a higher rate in an instructional setting. However, the fact that a majority of a language’s elements are hard to learn in an explicit way will eventually lead to a lower level of attainment than that of children.

What should I choose for my children?

When parents are trying to decide whether their children should start learning a second language as early as possible, it’s important to consider what context they will do so in. As Carmen Muñoz (2000) stated, an early start leads to higher chances of native-likeness as long as children are receiving intense, implicit and frequent exposure. This is so, because they are being given the chance to use their innate abilities to learn. However, as we’ve seen, this kind of learning needs to happen in the most natural way possible. When children are asked to learn a language in a very structured way from a very early age they’ll be asked to use skills they don’t possess yet and won’t be developing till later on in life. Moreover, the development of these skills that are fundamental for every type of learning, happen roughly at around the same age for every child and can’t be rushed.

What this means is that learning a second or third language from an early age will provide children with a great social, cultural and academic advantage as long as it’s done in the most natural and communicative way possible. When this is not the case it can lead to frustration and endanger a child’s motivation to learn. Asking them to understand and explicitly memorise, rules, patterns and long vocabulary lists would be asking them to do something they can’t do yet,

How can this be done in a classroom setting?

Project based learning and active methodologies are great ways of trying to replicate real-life situations and making learning meaningful and natural. Using stories for learning a language, in the same way native children would, can also be a way of creating a rich and natural learning environment.

MORE LIKE THIS:

-

10 Tips to support dyslexic students during writing tasks

-

Guidelines for marking dyslexic students’ work

-

The dyslexia-friendly language classroom

-

Tips to make reading tasks accessible for students with dyslexia

-

Is it possible to correct language mistakes during project-based learning?

-

Inclusive assessment for the English language classroom

-

Learning languages can benefit neurodivergent learners

-

Challenging gender bias in the classroom

-

How to help develop a child’s language without screens

-

Teaching English to Visually Impaired Students

-

What does an inclusive ESL classroom look like?

-

Teaching English to visually impaired students online

-

5 Easy classroom routines to increase language exposure

-

How project-based learning can make your lessons more inclusive

-

Do men and women speak differently?

-

Special educational needs and second language acquisition

-

How can Universal Design for Learning help with Language Teaching?

Subscribe for more posts like this

Speaker's Digest

Speaker’s Digest wants to make language learning accessible to all regardless of origin, socioeconomic background or learning styles and needs.

Get in Touch

Who We Are

Proudly Powered by WordPress

Leave a comment